On a chilly Sunday afternoon in August 1832, the waters of Woolloomooloo Bay bore witness to a strange and striking scene. A small community of Baptists had already existed in the colony for a little over a year, meeting in the Long Room of the Rose and Crown Inn. But on this Sunday afternoon they took their gathering out of doors for the first recorded baptism of believers in the colony’s history. When I think about the symbolism of baptism and its place within our history as Australian Baptists (as National Baptism Week encourages us to do), this is the scene my mind turns to. I hope you find it as intriguing and inspiring as I do!

Ken Manley narrates the story of the occasion on the opening page of his history of Australian Baptists, highlighting both the courage of the participants and the amusement that they provided for the watching crowd:

Two “females” were baptized in Woolloomooloo Bay near the Domain by John McKaeg, the first Baptist minister to come to Australia. Evidently a mother and daughter, but whose names are unrecorded, these two pioneer Baptist converts braved the ridicule of some seventy spectators. McKaeg, wearing a long black garment with a belt around his waist, harangued the intrigued crowd in his thick Scottish brogue “for some time” with “extraordinary energy and violent gesticulations” before leading the older woman into the water. He then took hold of her, proclaimed her baptized in the name of the Holy Trinity, [and] threw her backwards in the water, “from which she rose completely drenched.” The daughter was “soused” in the same way. The preacher pronounced the benediction.

The public ordeal was not over. Whilst McKaeg, assuming a suitable gravity, changed into dry clothes behind a rock the ladies sought to do the same behind another rock but mischievous boys went to peep, “cracked a multitude of jokes” and with a great deal of hooting and laughing, had a great day’s fun.1

Three weeks later, McKaeg and his fellow-Baptists were back in Woolloomooloo Bay, with three more converts ready to undergo baptism. This time the crowd of onlookers was several hundred strong, and the solemnity of the occasion was disturbed by an “underwater intruder,” inebriated and half-naked, who grabbed McKaeg’s leg and attempted to pull him under. McKaeg soldiered on, armed with a tree branch to ward off others who might attempt something similar, and the converts were successfully immersed. The Australian reported the story with glee, under the headline, “Adventure Extraordinary. Sermonising Afloat. Saline Baptism.”2

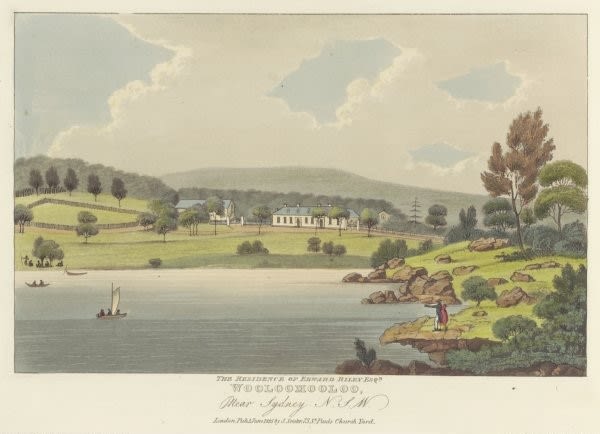

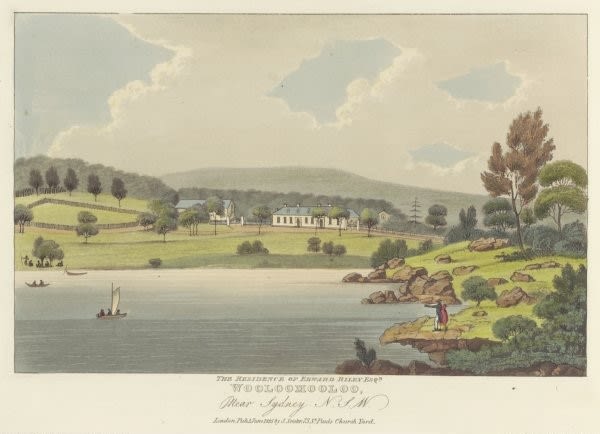

The Residence of Edward Riley, Esq.,

Wooloomooloo near Sydney, N.S.W

Joseph Lycett 1825

It did not take long for Baptists in Sydney to start creating more sheltered, comfortable and dignified places in which they could conduct their meetings and baptise converts to the faith. Within a few weeks an appeal had been launched for funds to build a Baptist chapel and a request was made to the governor for a grant of land. Eventually, in 1836, the first Baptist chapel was opened, and was described by one observer as “an excellent specimen of colonial workmanship, in the Grecian style.”3

By the time my own church, Petersham Baptist, erected its building half a century later, the social status and aspirations of its members were reflected in a stately, gothic-style structure built of honey-coloured bricks, in a fashionable, leafy street a block back from the main road. The land and building were paid for with the help of generous financial support from Sir Hugh Dixson, a prominent tobacco merchant and philanthropist and a founding member of the church. That building was soon enlarged with the addition of a grand transept, to which, in turn, was added a stately organ with three ranks of pipes, prominently located beneath an arch on which was written, in giant gilded lettering, “Worship the Lord in the Beauty of Holiness.” Baptisms in subsequent decades took place within a purpose-built baptismal pool, nestled beneath the organ pipes and the arched golden lettering above them, and that continues to this day to be the pool in which most of our baptisms take place.

Photo: Peter Jewkes

There is something undeniably beautiful about a baptistry like that as a location for the baptism of a new believer to be performed. New believers declare their faith in Christ and dramatise the dying and rising of Jesus amidst the gathered community of the local church that they are joining, within the history-haunted space in which they and their predecessors have convened across the decades for the same purpose. Old and young crowd together around the pool beneath the organ pipes, parents clutching onto the hands of toddlers as they lean forward to see what is in the water, and all rejoice together at another reminder of the gospel and the power of God to save.

But in the comfort and the beauty of a space like that it is perhaps a little too easy to forget the starkness of the symbolism that is at the heart of the act we are performing.

Baptism is, after all, about the ordeal that Jesus went through on our behalf, and about our union with him in his dying and rising. It is a signpost to a gospel that is to be proclaimed in all the world. And the community into which believers in Jesus are called to enter is not a community that is promised a safe, comfortable or dignified existence. As much as I love so many of the layers of the symbolism that a baptistry like the one in our beautiful old nineteenth-century building carries, I sometimes wonder what we’ve lost in gaining them. Perhaps, from time to time, it would be good for us to go back to something a bit more like that first recorded baptism in the waters of Woolloomooloo Bay, with all its raw, exposed, confronting reminders of the Jesus whom we are following and the life to which he calls us.

Wherever and however you end up celebrating it, I hope that National Baptism Week gives you a chance to think again about the Jesus who died, was buried, and rose again for us, about the union with his death and resurrection that we are called to in the gospel, about the community we are welcomed into as his people, and about the mission he has entrusted to us in his world. Happy Baptism Week!

1Ken Manley, From Wolloomooloo to “Eternity”: A History of Australian Baptists, 2 vols. (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006), 3, quoting from contemporary articles in the Australian and the Sydney Gazette.

2Manley, From Wolloomooloo to “Eternity”, 3-4.3From Wolloomooloo to “Eternity”, 25.